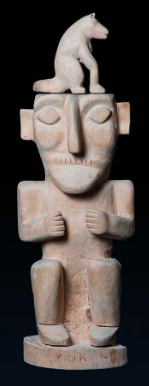

Blind Contour Drawing #37 “Wolfman” Kitty Smith

After several interviews with Kitty Smith, author Julie Cruikshank realized that the best way to connect with Smith was through stories. “To a large extent,” Cruishank observes, Smith’s “evaluation of other people … is based on their storytelling abilities.”

Storytelling is inseparable from Smith’s life and livelihood. She understands her own personal history as intertwined with the history of her communities and the cultural origin stories—tales of wolves, crows, women, and children—that nourished her upbringing. Spoken in her first languages of Tlingit and Athapaskan (Tagish) and—later—in English, these narratives are Smith’s method of talking about people and places.

Born in 1890 near the mouth of the Yukon’s Alsek River, the early years of Smith’s life were dramatically impacted by the Klondike gold rush, which peaked between 1896 and 1898. Her mother’s brother, along with three other Tlingit men, was accused of shooting a white prospector. Smith explains the shooting itself as customary revenge for the poisoning of two Tlingit men by prospectors, but the punishment on her uncle was severe: all four men were tried for murder; her uncle and another man were executed, while the other two died in hospital. Smith’s mother travelled to Marsh Lake, the home of her own mother’s family, rocked by shock and grief. While there, she died of an influenza epidemic.

Left without a mother, Smith was largely raised by her father’s family, who taught Smith to be a skilled trapper as they travelled along Yukon rivers. Raised to a high status through a potlatch ceremony, a strong marriage was secured for her once she finished a lengthy seclusion through puberty. However, Smith was dissatisfied with the marriage; her husband, she claims, was unfaithful and unskilled. She made the decision—shocking for the time—to leave him and to live with her mother’s family, a “Crow” family, according to Tlingit kinship affiliations. Here, she developed close bonds with her grandmother, who eventually secured a better marriage with Billy Smith. The couple had six children, to whom they taught hunting, trapping, fishing, sewing, and other skills.

But Smith never relied on her husband as a means of support. At a time when women were neither primary breadwinners nor carvers, Smith was both, and she was fiercely independent. In the 1930s, she realized how much Canadian soldiers would pay for winter gear, so she used muskrat skins to sew mitts and mukluks. She also began carving small poplar totems of the animals that populated the stories she grew up with. Her husband would sometimes write short pieces to accompany the figures, such as “The Wolf Man,” which she affixed to the bottom of her Wolf Man carving. Later, she published a book of stories, entitled Nindal Kwädindür / I’m Going to Tell You a Story. The collection is as much homage to her reverence for narrative as are her carvings.

Smith died in 1989. At that time, she was one of the last people to remember the impact of the gold rush and the construction of the Alaskan highway on Tlingit and Athapascan people. But although her early life bore the ruptures brought by western economic and environmental intrusions, she remained steadfastly devoted to and defined by the stories and relationships of the multigenerational lines of her family.

Born: 1890, Yukon

Died: 1989

Sources:

Cruikshank, Julie. Life Lived Like a Story. U of British Columbia P, 1990.

“How People Got Fire: Study Guide.” National Film Board of Canada. http://lss.yukonschools.ca/uploads/4/5/5/0/45508033/hpgf_guide.pdf

Kwanlin Dün First Nation. Listen to the Stories: A History of the Kwanlin Dün People. A Kwanlin Dün First Nation Publication, 2013.

Tukker, Paul. “Flea Market Find Inspires New First Nations Art Exhibition in Yukon.” CBC News, 14 May 2017, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/kitty-smith-carving-flea-market-exhibition-whitehorse-1.4113543