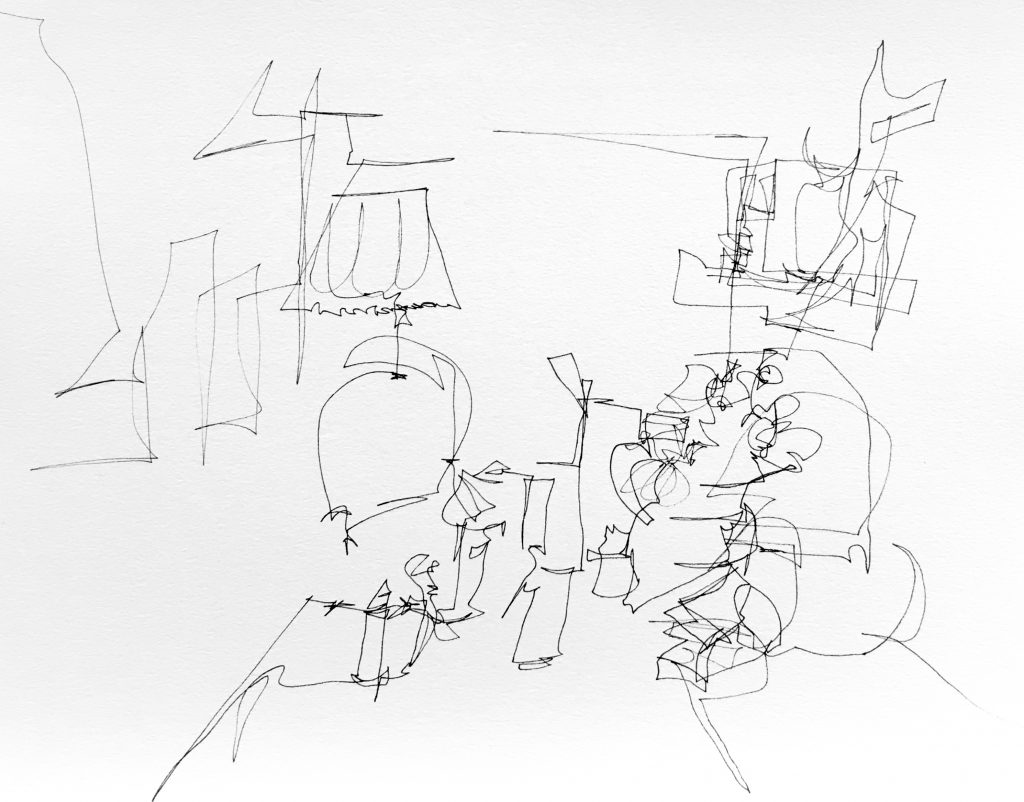

Blind Contour Homage – “Interior” Molly Lamb Bobak

In her seventies, artist Molly Lamb Bobak recalls Mary Williams with warmth and admiration: “She never kept a lot of baggage with her,” she reminisces, admiring the independence of her mother, who lived with but never married Bobak’s artist father, Harold Mortimer-Lamb—an unconventional arrangement for the 1920s.

Like Mary, Bobak’s later life was filled with gardening and living lightly. She parted with most of her paintings once she’d finished them, so that a 1990s retrospective of her life’s work prompted her delight at being reunited with “old friends.”

Bobak is remarkable for the vibrancy of her attitude as she broke barriers set before female artists of her generation. After graduating from Vancouver’s School of Art in 1941, Bobak registered in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC), jokingly called the “Quacks.” For three years, she travelled from training camp to training camp across Canada, at every opportunity begging her commanders to be considered for the position of war artist, a role no Canadian woman had ever held.

During these mid-war years, Bobak kept a most unusual diary, formatted as a mock newspaper and filled with sensational headlines about her daily experiences. Her first caption—“GIRL TAKES DRASTIC STEP!”— about enlisting is followed by years of entries that, on one hand, caricature her attempts to navigate military rules and, on the other hand, critique the institutional norms she was constrained to obey. The light-hearted sketches illustrating these journals are matched by the paintings she produced during this time; on one colourful canvas, she portrays herself skipping with a case of beer through the streets of Toronto.

At last, Bobak’s appeals landed on listening ears; in 1945, she became Canada’s first female war artist, and was sent overseas to document Canadians’ experiences at war. Bobak’s art from this period offers a glimpse of women in the war that no other Canadian artist could provide: images of Canadian servicewomen working as typists, drivers, seamstresses, launderers, dishwashers, and clerks—the only jobs available to women serving in the army.

Along with these portraits of military women, Bobak’s art is remarkable for her emphasis on community and friendship. Her scenes are public: women in the foreground, soldiers gathering in crowds—in bustling city squares, on fields, in gas masks, or at a canteen. These pieces focus on the energy of camaraderie that characterized her military service, as well as much of her life afterwards.

It was during the war that Molly Bobak met her husband, painter Bruno Bobak. Returning to Canada, they both worked as artists in Vancouver, travelling back to Europe for several years before finally settling in Fredericton.

Even in these post-war years, Bobak remained interested in the idea of crowds. She was frequently drawn to flowers and interiors, insisting that they were not so different from her earlier subjects: “Poppies are like crowds. They move in the wind. You don’t organize them; you don’t settle them into something. You paint them as they are: blowing or moving or dying or coming to birth. That’s how it is with my crowds.”

After her death at the age of 94 (outliving her husband by only two years), a friend celebrated her life and work, as well as her zeal for friendship and inclination to laughter: Molly’s art, he remarked, “expressed the sheer joy of living in a community.”

1920 – Vancouver, B.C.

2014 – Fredericton, NB

Exhibition Dates for this series.

Sources:

Freedman, Adele. “A Loyalist Bastion Bathed in Light.” The Globe and Mail, 1982 April 10.

“Molly Lamb: A Retrospective.” CBC Digital Archives. 1993 November 29. https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2414705964

Schaap, Tanya. “‘Girl Takes Drastic Step’: Molly Lamb Bobak’s W110278—The Diary of a CWAC.” Working Memory: Women and Work in World War II, eds. Marlene Kadar and Jeanne Perreault, Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2015.

Smart, Tom. “An Artistic Duo with Extraordinary Gifts.” Telegraph-Journal, 2018 June 23.