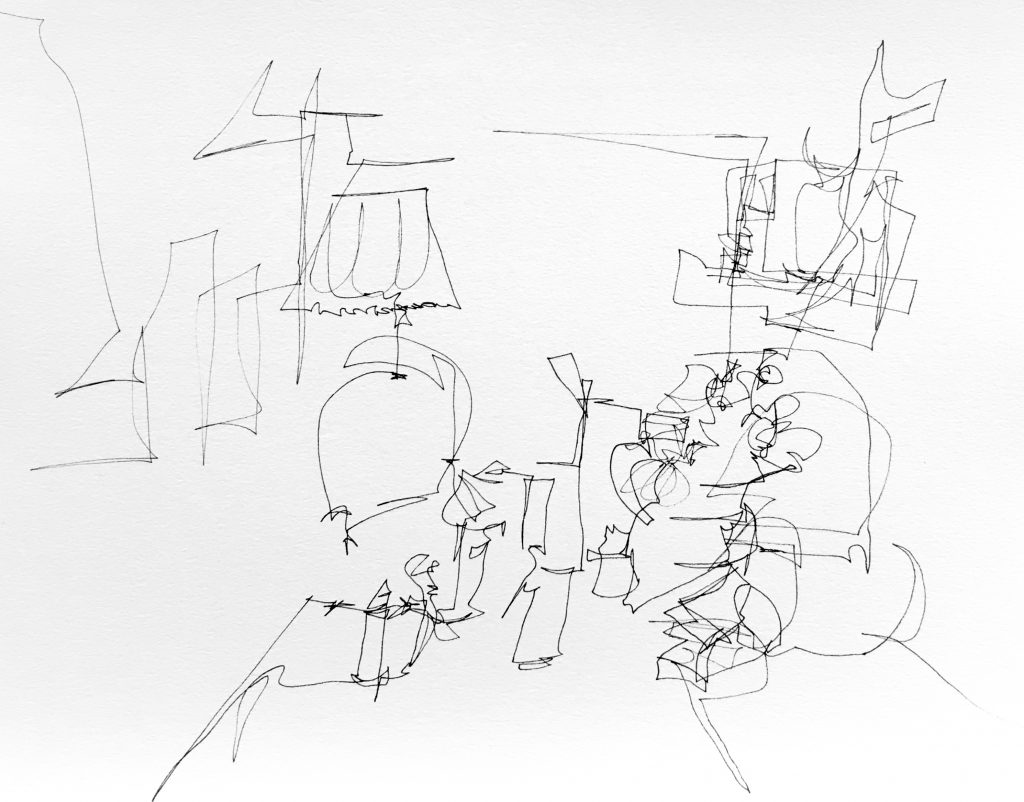

Blind Contour Drawing #39 “Pemberton Valley” Emily Carr

Emily Carr is one of the most widely celebrated and recognizable Canadian painters. Strongly associated with the Group of Seven, many of her works represent the cultural identity of British Columbia—its natural landscapes, its historical development, and its indigenous heritage. But Carr’s legacy was not always so certain.

The eighth of nine children, Carr was raised by a domineering British father, who taught her that women ranked well below men, and who developed in his daughter an abhorrence of physical intimacy. Upon her parents’ deaths, Carr was left with a strict and controlling sister, who rebuked Carr for her interest in art. Thereafter, Carr rejected traditional expectations, making up her own rules and manners as she forged a new path.

In fact, it is hard to know whether obstinacy and eccentricity helped or hindered her success. During much of her lifetime, public response to Carr wavered between two unfortunate extremes: disregard and dismay. Despite her fine arts education in San Francisco, London, and Paris, Carr’s paintings were at first unpalatable to western Canadian audiences, who resisted the revolutionary modernist and post-impressionist trends she’d learned in Europe. And because her physical and mental health frequently suffered (she spent many months in European “sanatoriums”), she gained a reputation for volatility. Her reception was probably not helped by her public behavior: she smoked and swore, walked around with a pet monkey on a chain and a rat in her pocket, and had a hot temper, which was frequently unleashed upon the tenants of her boarding house, “The House of All Sorts.” This ignominy, as well as the economic hardships of World War I, meant that Carr struggled to make ends meet. She produced very little art in her middle age, partly because students would rarely study with her, and partly because she had to work so hard as a landlady.

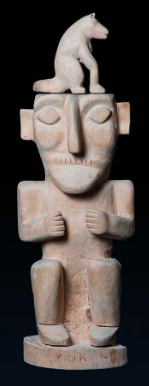

Despite these antagonisms, Carr persisted in pursuing her own passion for western landscapes and indigenous cultural heritage, and this tenacity was ultimately rewarded by broad celebration in her final years. When fame finally materialized, the work she had produced over her lifetime came to light, including the paintings produced as a younger woman during her frequent sojourns to First Nations communities along the west coast, where she painted totem poles in their natural settings. She was determined to document the poles before they disintegrated, and to record the indigenous people she encountered, recognizing the threat to their culture and lives by disease, poverty, and government policies.

In 1927, Carr’s work was “discovered” by Marius Barbeau and Eric Brown, who convinced Carr to allow her paintings to be featured in an exhibition on West Coast indigenous art at Canada’s National Gallery. Carr’s visit to Ontario for this grand entrance into eastern Canada’s art scene enabled her meeting with Lawren Harris and other Group of Seven members, who guided Carr’s transition from totem pole pieces to landscape paintings of the mountains and forests of the lower mainland and Vancouver Island, which were painted while she travelled through wilderness campsites in her caravan, “The Elephant.” In her sixties, she turned to creative writing; her essays and short stories were published in seven highly successful collections before and after her death in 1945. It was only in these final years that Carr earned enough to survive without renting out rooms, breeding dogs, or taking on art students. At last, she was rewarded with the recognition her work merited: in addition to receiving the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction, her paintings were bought by Canada’s National Gallery and the Vancouver Art Gallery, and are still exhibited in esteemed galleries around the world.

Born: 1871, Victoria, B.C.

Died: 1945, Victoria, B.C.

Sources:

Forster, Merna. 100 Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces. Dundern Press, 2004.

Klerks, Cat. Emily Carr: Adventures of a West Coast Artist. Heritage House, 2015.

Shadbolt, Doris. The Art of Emily Carr. Douglas & McIntyre, 1979.

Thom, Ian M. Emily Carr Collected. Douglas & McIntyre, 2013.